Long before Roger Deakin used the term in 1999, youth hostels promoted wild swimming. From work in progress…

In Britain today we rarely carry water. We rarely understand its weight and its burden.

One litre of water weighs nearly 1kg. If a shower uses about 50 litres of water that would be a heavy load to carry.

In 1936, in rural places, water had to be carried from rivers, streams, springs, wells and pumps. Water was cold, unless heated on a stove or an open fire.

Lucky men

At East Meon youth hostel in Hampshire, a young woman took water from a well in a bucket and carried it back to the hostel for cooking and washing. She drew a picture of the well, a handle, rope and bucket, like something from a fairy tale.

In youth hostels in the 1930s washing was rudimentary. It happened standing over enamel basins in bedrooms.

Women often had the better facilities, like basins in bedrooms. Men were lucky if they could wash at a trough, in a barn or a yard.

Some job

Sometimes water was lacking. Cicely Cole, at a farmhouse in Somerset, found her “only chance of a bath was a swim in sea or river”. She walked across fields to get it.

At Bala in Wales, Berta Gough “had to go to the river for all the water for washing etc. Some job!”

Farm drains

If water for washing was not provided, water for drinking was essential. Pennant Hall, in Wales, opened as a youth hostel in time for Christmas 1930 but the “sanitation was most primitive”. Drains from a farm ran into the river, from which the hostel drew its drinking water, and forced the hostel’s end.

Bridges in Shropshire was one of the first youth hostels to open in 1931. A spring supplied drinking water and washing water came from a stream.

Hand pumps could supply water. Fred Catley did his bit at an outside pump that supplied water for everybody at Steps Bridge in Devon.

Hot luxury

Where there was no pump, distances travelled to fetch water could be long.

Water for the hostel at Gara Mill in Devon had to be carried up a steep, muddy path. Some avoided that and washed in the stream.

If water was limited, hot water was a luxury. Jane Ash mentions no baths at all during a week in the Peak District.

Better swimming

She was modest but youth hostels may have ignored luxury, in favour of economy and money saved.

A design thesis on youth hostels declared that “hot water should be supplied [only] where it can be afforded… One purpose built youth hostel, at Meashafn in Wales, only provided cold showers.

The same thesis recommended shower flows of one gallon (4.5 litres) a minute, about the same as today’s flows for an environmentally friendly shower. That would mean carrying 4-6kgs of water for a one minute shower.

None

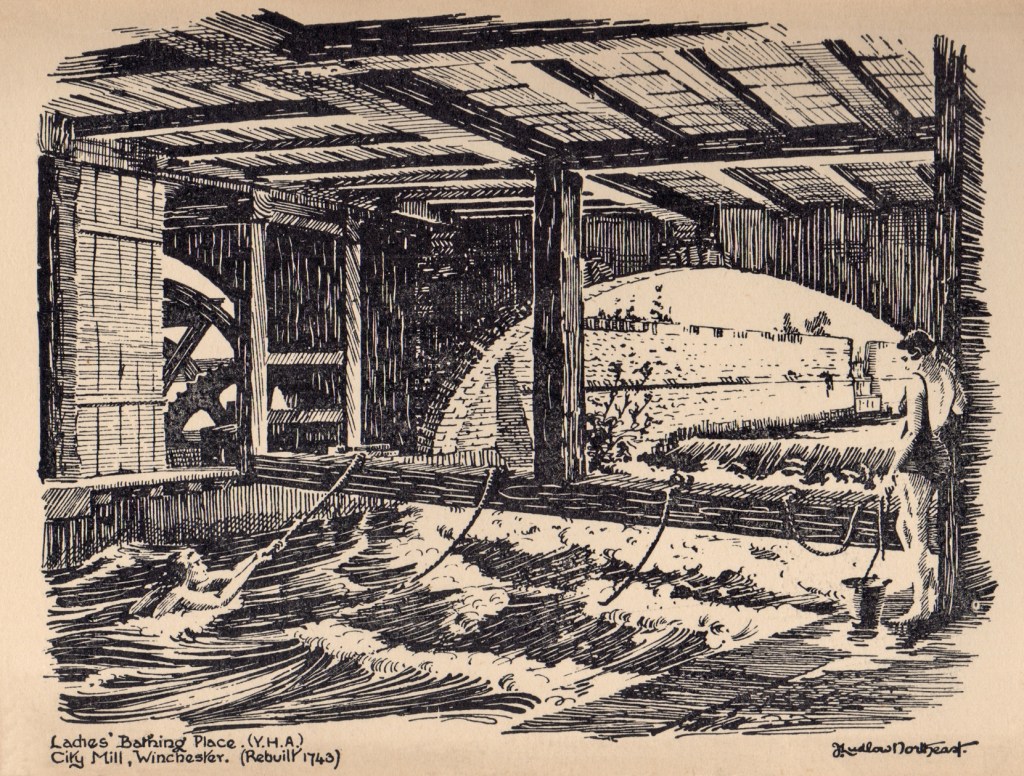

For those like Cicely Cole, hostels gave information on bathing in their listings in early handbooks.

The first youth hostel handbook in 1931 mentions bathing at two hostels. By 1932 that number had increased to four. The following year, eleven hostels included bathing in their listings. The number multiplied in following years.

But the bathing was not in showers or baths. River bathing, sea bathing, stream bathing, bathing in the sea and open air, bathing in sea water, lake bathing, and pool bathing all found their way into hostel descriptions. Some went as far as to state – no bathing.

Reading history

The term “bathing” is problematic. Bathing has two spellings, two meanings and two pronunciations. It can mean bathing as in washing or showering. It can mean swimming for pleasure.

Despite Cicely Cole swimming as a way of keeping clean, what the term meant for youth hostels and their users is not simple to decipher.

It seems more likely that bathing mentioned in youth hostel handbooks was swimming for pleasure. Swimming in lochs, lakes and rivers was part of the freedom and joy of holidays.

Grand pleasure

A fashion for outdoor swimming began in the period before 1914 but the 1930s was its heyday in Britain, when towns built lidos, part of a general enthusiasm for health and the outdoors.

Jane Ash and her friends carried swimming costumes and hoped to swim in Peak District rivers. None were appealing, and the weather was wet.

Isobel Brown “bathed” in Scotland for pleasure. She swam at Ratagan in hot weather when she could float in the warm water. She swam again the next morning, and that swim was even better because the water was so still.

She swam at Broadford, on Skye, and before breakfast again. When others wouldn’t get in the water, she swam, even in rough and choppy water. It was grand in the water she announced.

Liberation

In no sense did she swim to get clean. She swam because she loved the water and the views she had out in the water. She swam because she was a wild swimmer, before her time, enjoying the new found liberation of a touring holiday.

Notes

This post is from a work in progress, about the way we changed our holidays in the 1930s.

The first use of the term wild-swimming from the Oxford English Dictionary https://www.oed.com/dictionary/wild-swimming_n?tl=true

Design thesis on youth hostel design and showers from Horsfield, Alexander J, The Design and Equipment of Youth Hostels, 1940.

Shower flows today, from Government Buying Standards for showers, taps, toilets and urinals.

Diaries and records consulted in this blog:

- Historical listing of youth hostels, prepared by John Martin, 2024. Available here.

- Hilary Hughes, and Berta Gough journals, YHA Archive, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham.

- Fred Catley diaries, Bristol Archives, Smeaton Road, Bristol BS1 6XN.

- Isobel Brown journals, SYHA Archive, National Library of Scotland.

To obtain water, WELL (see what I did there?) into the mid 70’s, members at Woodys had to push a what can only be described as a dustbin on wheels downhill to a farmyard with a water tap in the hamlet of Ruckland.

Going downhill with an empty required little effort, but pushing a 40 gallon bin up a 1 in 5 hill was a challenge of immense fortitude.

Fortunately, by the time I was asked to manage there, the luxury of mains water had been connected.

Sounds very like the arrangement at Ilam Hall!

That experience must well predate my stays there….bit incongruous for such a stately property (now) under the auspices of National Trust?

Sorry, got that wrong I meant Hartington Hall, not Ilam! And yes, it certainly predates our time.

Happy Christmas Duncan (we never did get that second cup of tea!)

Lovely memories of Staindale YH (North Yorks. Moors) in 1962, fetching buckets of water from the bottom of the field in a heavy snowstorm! So much snow, I could cross the stone walls without touching them!

Thanks for that info on Staindale. I was looking at the 1930s but it looks like difficulties getting water in rural places carried on after that time!

Staindale YH was a cosy cottage with basic facilities. That day I walked up from Thorton-le-Dale as the road over the moor was blocked by snow. On arrival, being already snow-covered, I was presented with 2 buckets to be filled with water before I was allowed in! The earliest hostel duty I was ever given. The warden was a good friend of mine, so no problem!